Modern art isn’t just about strange paintings or sculptures that look like they were made by a child. It’s a radical shift in how artists saw the world-and how they wanted you to see it too. Starting in the late 1800s and stretching through the mid-1900s, modern art broke every rule you learned in school. No more perfect landscapes. No more idealized portraits. Instead, artists started asking: What if color could feel emotion? What if a painting didn’t need to look real to be true?

Rejection of Tradition

Before modern art, art was mostly about telling stories-religious scenes, royal portraits, historical battles. It had to be beautiful, detailed, and technically perfect. But by the 1860s, a new generation of painters started saying: modern art doesn’t need to copy reality. It needs to express something deeper.

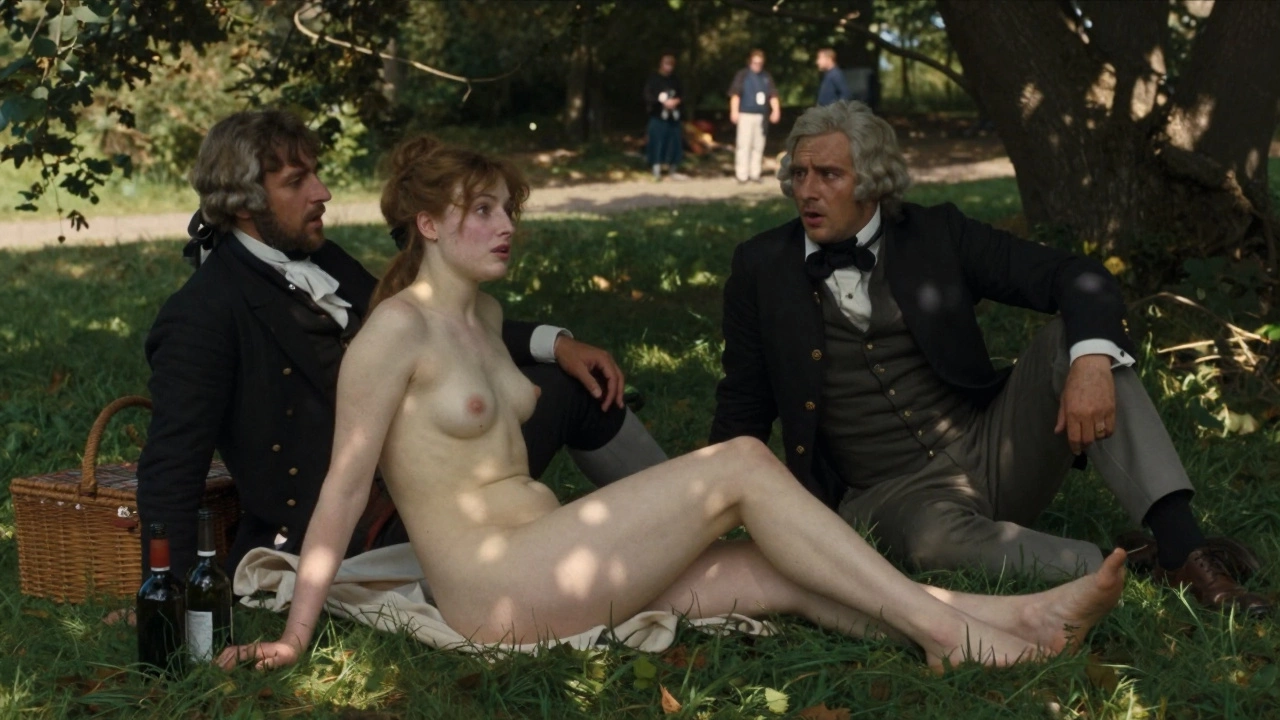

Edouard Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe (1863) shocked Paris because it showed a naked woman having a picnic with fully dressed men. No mythological excuse. No divine justification. Just a woman, in the present, unapologetic. That painting wasn’t about technique-it was about attitude. And it opened the door for everything that came after.

Abstraction: Letting Go of the Real

One of the biggest leaps in modern art was letting go of recognizable shapes. Artists began asking: Can you feel joy without seeing a smiling face? Can you sense chaos without a storm cloud?

Wassily Kandinsky, a Russian painter, is often called the father of pure abstraction. In 1910, he painted his first non-representational work. No trees. No people. Just swirls of color and lines. He believed colors had spiritual vibrations-yellow was sharp and loud, blue was calm and deep. His paintings weren’t meant to be looked at like photos. They were meant to be felt like music.

Abstraction didn’t mean random splashes. It meant intention. Every brushstroke was chosen to carry emotion, rhythm, or tension. Artists like Kazimir Malevich took it further with Black Square (1915)-a single black square on a white canvas. To some, it was nonsense. To others, it was the ultimate statement: art doesn’t need to show anything. It just needs to exist.

Expressionism: Feeling Over Form

While abstraction focused on form and color, expressionism focused on raw emotion. German artists like Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Emil Nolde didn’t care if their figures looked realistic. They wanted to show fear, anxiety, alienation-the inner turmoil of modern life.

Kirchner’s Street, Dresden (1908) shows people with jagged edges, distorted faces, and clashing colors. The city isn’t peaceful-it’s electric, overwhelming, almost violent. This wasn’t about documenting a street. It was about how it felt to walk through it in 1908: lonely, fast, confusing.

Expressionism didn’t need to be ugly to be powerful. It just needed to be honest. And that honesty changed everything. Later, American artists like Jackson Pollock took this further-not with faces, but with movement. His drip paintings weren’t about what they looked like. They were about the energy of making them.

Cubism: Seeing Multiple Angles at Once

Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque didn’t just paint what they saw. They painted what they knew. In Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), Picasso broke the human face into sharp angles. One eye looks front, the other side-on. The nose is a triangle. The body is a collage of viewpoints.

Cubism rejected the single-point perspective that had ruled Western art since the Renaissance. Instead, it showed multiple moments in time, multiple ways of seeing, all at once. It was like taking a photograph, then cutting it up and reassembling it while walking around the subject.

This wasn’t just a style. It was a philosophy. Reality isn’t fixed. Perception changes depending on where you stand. Cubism forced viewers to become active participants-to piece together the image in their minds, not just passively receive it.

Surrealism: Dreams as Reality

After World War I, many artists felt the world had lost its logic. Surrealism was born from that feeling. Led by André Breton, surrealists turned to dreams, the unconscious, and Freud’s theories to create art that defied reason.

Salvador Dalí’s melting clocks in The Persistence of Memory (1931) aren’t about time running out. They’re about time losing its grip. The landscape is barren, quiet, eerie. The clocks aren’t broken-they’re soft, like cheese. It’s not a nightmare. It’s a memory of how time feels when you’re half-asleep.

René Magritte’s The Treachery of Images (1929) shows a pipe with the words Ceci n’est pas une pipe-“This is not a pipe.” Of course it’s not a pipe. It’s a painting of a pipe. The painting is a symbol. The symbol is not the thing. Surrealism didn’t want to trick you. It wanted to wake you up to how language and images lie to us every day.

Industrial Influence and New Materials

Modern art didn’t just change what artists painted-it changed what they painted with. The rise of factories, steel, glass, and plastic gave artists new tools. Marcel Duchamp took a mass-produced urinal, turned it upside down, signed it “R. Mutt,” and called it Fountain (1917). Was it art? The art world argued for decades.

That question changed everything. Art didn’t have to be handmade. It didn’t have to be beautiful. It just had to make you think. Duchamp’s readymades forced museums to ask: What makes something art? Is it skill? Is it intention? Is it the context?

By the 1950s, artists were using industrial paints, plywood, wire mesh, even neon lights. David Smith welded steel into abstract sculptures. Louise Nevelson built towering black wooden assemblages from discarded crates. Art was no longer confined to canvas or marble. It could be anything, anywhere.

Art as a Reflection of Society

Modern art didn’t exist in a vacuum. It responded to wars, revolutions, urbanization, and technology. The chaos of World War I pushed artists toward abstraction and surrealism. The rise of cities made expressionism feel urgent. The spread of photography freed painting from the duty of realism.

Women artists like Georgia O’Keeffe painted giant flowers as if they were landscapes-turning the intimate into the monumental. African American artists like Jacob Lawrence used bold colors and simplified forms to tell stories of migration and struggle. Their work wasn’t just art. It was testimony.

Modern art was never just about aesthetics. It was about questioning power, identity, perception, and truth. It asked: Who gets to decide what’s beautiful? Who gets to speak? What counts as real?

Why Modern Art Still Matters Today

When you see a graffiti mural, a digital collage, or a minimalist sculpture in a museum, you’re seeing the legacy of modern art. Today’s artists still ask the same questions: Can color express grief? Can a pile of trash be sacred? Can a photograph be a lie?

Modern art didn’t end in the 1950s. It just changed its clothes. The ideas it started-rejecting tradition, embracing subjectivity, using new materials, challenging the viewer-are still alive. Every time someone says, “My kid could paint that,” they’re actually reacting to the same shock that Kandinsky and Duchamp caused over a century ago.

Modern art isn’t about understanding everything. It’s about feeling something. It’s about being unsettled. It’s about realizing that the world isn’t as simple as it looks-and that’s okay.

What makes art "modern"?

Art is called "modern" when it breaks from traditional techniques and subjects to explore new ways of seeing, feeling, and expressing. It emerged around the 1860s and lasted until the 1950s, defined by movements like Impressionism, Cubism, Surrealism, and Expressionism. Modern art values personal vision over realism, experimentation over perfection, and ideas over decoration.

Is abstract art just random splashes of paint?

No. Abstract art is highly intentional. Artists like Kandinsky, Mondrian, and Pollock carefully chose colors, shapes, and movements to evoke emotion, rhythm, or spiritual ideas. Even when forms aren’t recognizable, every element is deliberate. A Pollock drip painting might look chaotic, but it was made with controlled gestures, rhythm, and timing. It’s not about skill in drawing-it’s about skill in feeling.

Why did artists start using everyday objects as art?

Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain (a signed urinal) challenged the idea that art must be handmade or beautiful. He wanted people to question: What makes something art? Is it the object? The artist’s choice? The context? This opened the door for conceptual art, where the idea matters more than the object. Today, this idea shapes everything from installations to digital art.

Can modern art be understood without art history knowledge?

Yes. Modern art doesn’t require a degree to feel. You don’t need to know the name of every movement to be moved by a painting. Ask yourself: What does this make me feel? Does it feel calm, angry, confused, excited? Your reaction is valid. Art history helps explain why it was made-but your experience is what makes it alive.

How is modern art different from contemporary art?

Modern art refers to work created roughly between the 1860s and 1970s, focused on breaking from tradition and exploring new forms. Contemporary art is what’s being made today-after the 1970s. It’s more diverse, global, and often uses digital tools, video, performance, and social media. Modern art laid the foundation; contemporary art builds on it.

If you’ve ever stared at a strange painting and thought, “I don’t get it,” you’re not alone. But that moment of confusion? That’s exactly where modern art does its work. It doesn’t give you answers. It gives you questions. And sometimes, that’s more valuable than any masterpiece ever could be.