Ever wondered why some paintings just seem to grab your eye with grit and mystery, while others end up flat no matter what you do? There’s a sneaky trick hiding in plain sight—scrubbing. It sounds brutal, but it’s actually one of art's most hands-on, freeing moves. Forget dainty little brushes kissing the canvas. Scrubbing’s about friction, energy, and sometimes being willing to mess things up just enough to find the magic.

What Is Scrubbing in Art and Why Do Artists Use It?

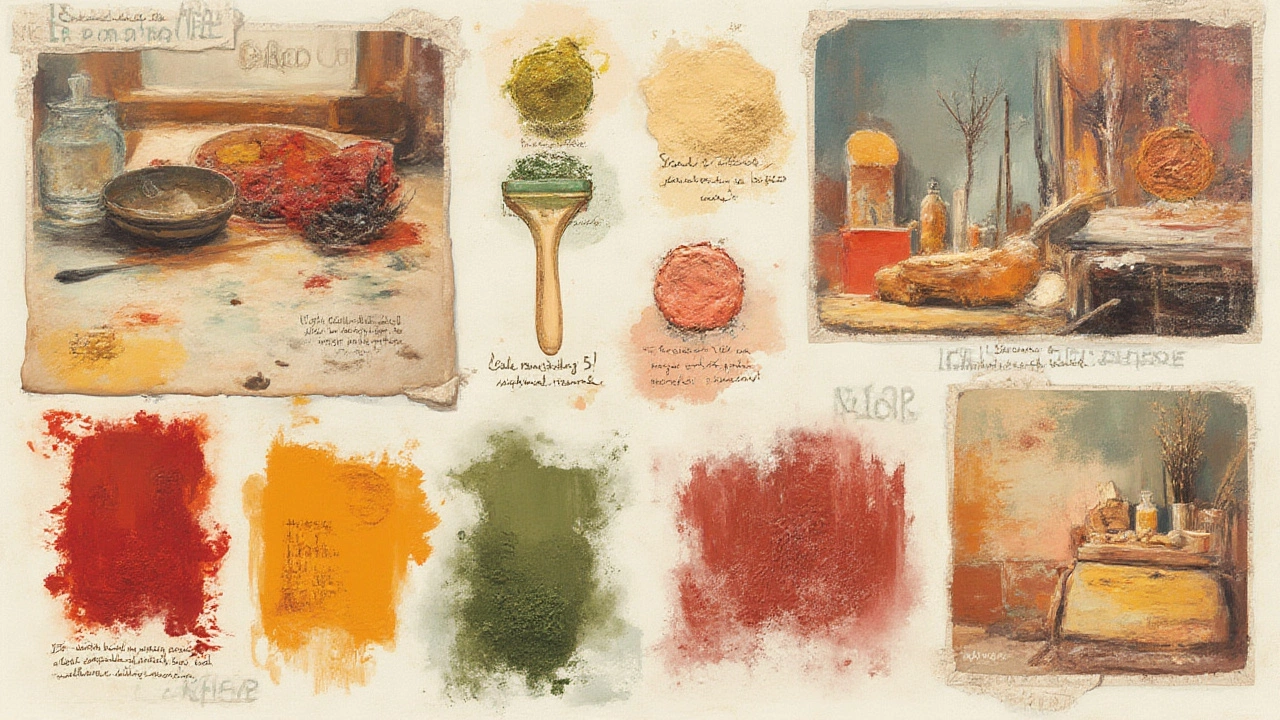

If you haven’t watched someone take a battered old brush to a painting and literally rub paint onto the surface, you haven’t experienced the wild charm of scrubbing. The scrubbing technique means using a brush (often stiff and dry) to push, pull, or even scour wet or dry pigment across a canvas or paper. It’s not about gentleness—it’s about grinding color in, lifting some off, and roughing up the surface. There’s no secret club, no special diploma. Anyone can try it, but artists who master it unlock extra ways to make their paintings jump out at you.

At its heart, scrubbing changes texture. You get soft, blurry edges, scuffed areas that look worn, or skies that melt into each other. In portraits, it can create realistic skin transitions or battered backgrounds. In landscapes, scrubbing makes dirt, rocks, or mist feel real. And it’s not just for acrylics or oils—watercolor artists swear by it for lightening spots, softening hard lines, and correcting mistakes.

There’s some science to it. Scrubbing loosens pigment particles. Depending on the paper or canvas, it can even lift color off entirely. Good watercolor paper can handle a fair bit of abuse, but cheap stuff pills up quickly and leaves holes. Oil and acrylic pads are more forgiving, although stubborn paint layers might need extra elbow grease.

The main point: scrubbing isn’t about looking neat. It’s about giving up control just enough that the painting breathes. Here’s a wild fact—a 2019 survey of over 500 amateur and professional artists showed that over 71% used scrubbing at some stage, especially beginners tackling skies, rocks, fur, or clouds. It’s literally a universal hack, even if it’s more punk rock than most art school syllabuses let on.

Scrubbing: Materials, Tools, and How to Do It Right

You don’t need anything fancy to scrub. The only rule? Don’t use your favorite brushes. Scrubbing is hard on bristles. Most artists use old, worn-out brushes. Flat brushes or round ones with short, stiff bristles are perfect. Hog hair, cheap synthetics, and even makeup brushes you don’t care about can work. For watercolor, artists often snap up ‘scrubber’ brushes with tough white nylon bristles—they’re made to take a beating.

Other tools? Sponges can create big, soft textures. Old rags or even paper towels let you dab and drag color for extra grunge. There’s also a neat trick: dipping a toothbrush in paint and ‘scrubbing’ for wild, splattery effects.

The right surface matters. Quality matters for repeated scrubbing. Good 300gsm cold-press watercolor paper handles a lot. Cheap paper pills or tears, so if you’ve ever wondered why your painting turned fuzzy, you may have scrubbed too hard on the wrong support. Canvas, especially if well-primed, is basically scrub-proof—oil painters practically invented this technique for softening backgrounds or blending flesh tones.

Scrubbing happens at different stages. Here are some quick steps:

- Prep your brush—start dry or damp, not soaking wet.

- With watercolors, let your paint dry partially if you want to lift out color, or scrub on wet paper for blending.

- For acrylics and oils, scrub before the paint fully sets. Add a bit of medium (water for acrylic, odorless solvent for oils) if it gets sticky.

- Use a light hand at first—you can always rough it up more. Pressing too hard can damage your paper or canvas.

- Pick up pigment and drag it in circles, back-and-forth, or even in zig-zags for dramatic textures.

- Stop, step back, and see if you like what’s happening. The chaos can spark cool ideas.

Common mistakes? Going too hard, too fast. Heavy pressure on delicate paper leads straight to disaster. Using the wrong brush—it’s tempting to take your fancy Kolinsky sable to scrub just a bit, but you’ll regret it. Another big one is scrubbing with no plan. Sure, random marks can be great, but try to imagine where those rough textures might make sense. Skies, crumbling stone, reflections on water—they’re classic scrub zones.

Fun fact: British watercolorist Turner (the guy who basically invented painting fog and storms) was notorious for grinding, lifting, and wiping at his paintings. He’d sometimes use his handkerchief if no brush was handy.

Real-Life Uses: Fixes, Effects, and Mastery of the Scrubbing Technique in Painting

Scrubbing is more than just creating texture. It’s a go-to fix when things go wrong. Made a line too harsh? A bit of scrubbing softens it. Need to lighten a spot in watercolor without painting over it? Scrub and blot. Oil and acrylic painters use scrubbing to blend awkward transitions or add that scuffed-up, timeworn look that makes bricks, bark, and fabric believable.

Watercolor folks swear by scrubbing for lifting mistakes. Got a bloom (that white ring that sometimes forms when water pushes pigment out)? Wait for it to dry, then lightly scrub to smooth it. Some even use scrubbing to scratch sparkles into ocean paintings or pick out tree branches from tangled washes.

Acrylic and oil scrubbing looks a bit different. Because the paint layer is thicker, you can push colors together to get velvet-soft blends. It’s how a lot of portrait painters create subtle cheekbones and blurred backgrounds. Ever wondered how Bob Ross gets that soft fall of mist in his landscapes? Scrubbing. He’d use big, battered bristle brushes and pure chutzpah.

Some common subjects that practically demand scrubbing:

- Stormy skies—layered, smudged colors give clouds a real, moody feeling.

- Stone, bark, or concrete—rough, unpredictable marks make rigid manmade stuff pop.

- Animal fur—short, scrubbed brushwork mimics the randomness of animal coats.

- Misty backgrounds or reflections—nothing does “soft edge” like a good scrub.

- Correcting mistakes—you’re never stuck with an awkward edge if you can just scrub it away.

Here’s a table showing popular uses of scrubbing in different mediums and their effects:

| Medium | Common Uses of Scrubbing | Care Needed? |

|---|---|---|

| Watercolor | Lighten/lift areas, blur edges, correct mistakes | Yes — paper damage risk |

| Acrylic | Blend colors, add scuffed textures, soften backgrounds | Medium — good canvas helps |

| Oil | Unify rough sections, soften details, work ‘alla prima’ | Low risk — strong surfaces |

For real mastery, artists play around with pressure, direction, wetness, and brush types. You don’t have to go wild—sometimes, the best effect is just a quick scrub to ease an edge. But if you want to level up, try these tips:

- Test on a scrap piece to learn how your paper or canvas reacts.

- Save your oldest brushes for the job—a fresh one gets destroyed fast.

- Mix up the motion: use circles, criss-cross, or dabbing to see what feels right for the scene.

- Remember: less pressure on weak paper, more on sturdy surfaces.

- Don’t be afraid to wipe out whole sections if they aren’t working. Scrubbing is forgiving.

Mistakes will happen, but that’s part of the charm. Scrubbing teaches you to let go and find happy accidents. It adds energy that just can’t be faked with perfect little brushstrokes. Watch how pros like Sterling Edwards or Jean Haines use scrubbing in watercolor—they make it look like a dance, swooping in with a fierce brush, then coaxing out beautiful soft shapes.

The next time you see a painting with soft backgrounds, scuffed detail, or blended, dreamlike light, you’ll know the secret—someone went to war with a brush and won. Whether you’re a brand-new painter or have filled a hundred canvases, give scrubbing a serious try. It’s the fastest way to get from stiff and careful to loose and real.

Scrubbing technique opens the door to paintings with emotion and texture you never knew you could create. Ignore anyone who tells you it’s amateur; some of the greatest artists in history had paint under their nails from scrubbing. In the end, it’s not about perfection—art was never meant to be too clean anyway.